Are you a directive or a supportive leader?

Are you a directive or a supportive leader?

Are you a directive or a supportive leader? Answer a few quick questions to find out!

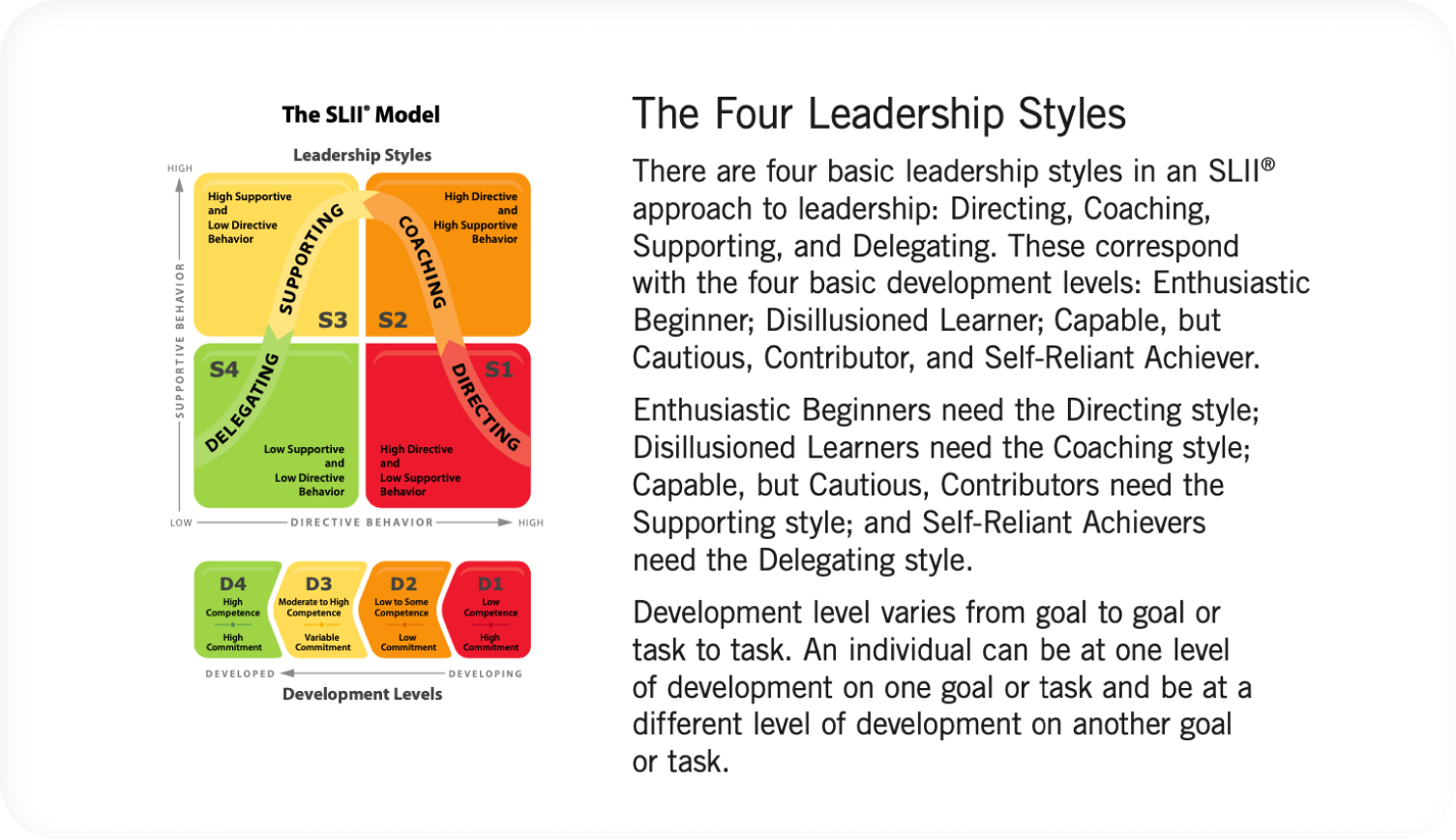

Forty years of Blanchard research has proven that the best leadership style is the one that matches the developmental needs of the person you’re working with. Is the direct report new and inexperienced about the task at hand? If so, more guidance and direction are called for. Are they experienced and skilled? In that case, they require less hands-on supervision and a more supportive style.

All of us are at different levels of development depending on the task we are working on at any given time. To bring out the best in others, leadership must be tailored to both the individual and the situation. Giving people too much or too little direction has a negative impact on their development.

Blanchard’s leadership development model, SLII®, takes a situational approach to effective leadership. This model is based on the belief that people can and want to develop and there is no single best leadership style to encourage that development.

The Three Skills of an SLII® Leader

To become effective as an SLII® leader, you must master these three skills:

1

Goal Setting

All good performance starts with clear goals. Clarifying goals involves making sure individuals understand two things: first, what they are being asked to do—their areas of accountability; and second, what good performance looks like—the performance standards by which they will be evaluated.

2

Diagnosing

You must diagnose the development level of each person on each of their goals and tasks by looking at two factors: competence and commitment. Competence is the sum of knowledge and skills an individual brings to a goal or task. Commitment has to do with a person’s motivation and confidence about a goal or task.

3

Matching

You must match your leadership style to the development level of the person you are leading. Oversupervising or undersupervising—that is, giving people too much or too little direction—has a negative impact on their development.

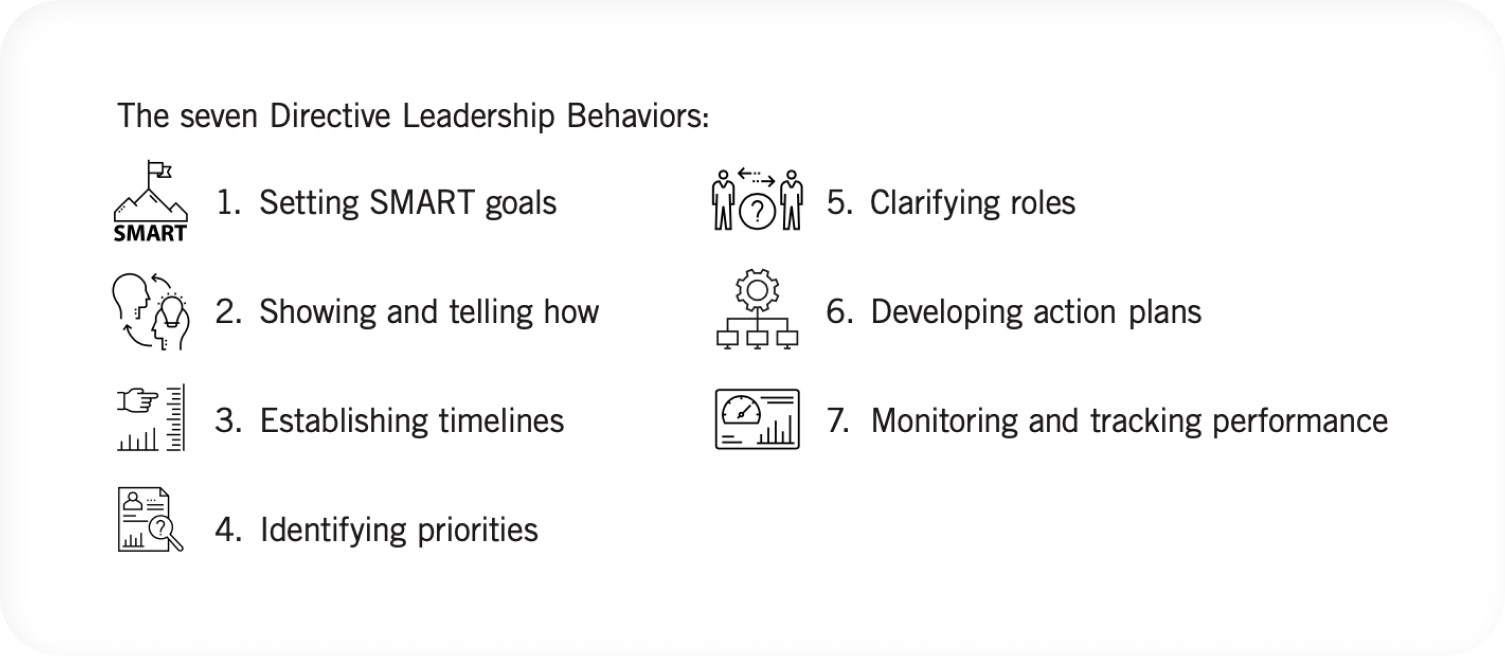

The 14 Micro-skills of Directive and Supportive Leadership

Effective leaders use two types of leadership behavior: Directive and Supportive. In our Leader Action Profile II assessment, we define Directive Leadership Behaviors as actions that shape and control what, how, and when things are done, and Supportive Leadership Behaviors as actions that develop mutual trust and respect, resulting in increased motivation and confidence.

Directive Leadership Behaviors

Directive Leadership Behaviors are actions that shape and control what, how, and when things are done. Leaders who have high Directive Leadership Behavior scores effectively structure, define, organize, teach, and monitor effectively.

Setting SMART Goals

The Setting SMART Goals subscale provides information about how frequently the leader meets with each team member to discuss and clarify the person’s goals as well as details about what the goal is and by when it is to be accomplished.

Our twist on this familiar concept switches up the order to focus on Specific and Trackable first. Once the S and T are in place, we use the other three SMART criteria—the R, A, and M—to check if the goal is Relevant, Attainable, and Motivating.

- Relevant. Is this goal important? Will it make a difference in your life, your job, or your organization?

- Attainable. A goal has to be reasonable. It’s great to stretch yourself, but don’t make a goal so difficult that it’s unattainable or you will lose commitment.

- Motivating. For you to do your best work, a goal needs to tap into either what you enjoy doing or what you know you will enjoy doing in the future.

All good performance starts with clear goals. If your people don’t know what you want them to accomplish, there is very little chance they will get there.

Are you good at setting SMART goals with your people? How would you evaluate yourself on the first critical leader behavior?

Showing and Telling How

The Showing and Telling How subscale provides information about how frequently the leader meets with each team member to describe and/or demonstrate how a goal or task should be completed.

As part of Blanchard's SLII® training, we teach that when someone is new to a task or goal, they need specific direction from their leader. One aspect of this direction involves the leader showing and telling the direct report how to do the task correctly. After all, if someone doesn’t know what a good job looks like, how can they be successful?

As simple as this seems, many leaders have a problem with showing and telling how. Why? In many cases, there is a fear they will be seen as a micromanager if they apply too much direction. Most leaders prefer to use a supportive style that asks the team member what they think would be best. But that style simply won’t work on a person who has no idea how to do the task. The leader is setting the direct report up for failure.

Direction feels perfect (and very supportive) when it is used with someone who is new to a goal or task.

How would you evaluate yourself on this critical leader behavior?

Establishing Timelines

The Establishing Timelines subscale provides information about how frequently the leader meets with each team member to discuss when goals or tasks are to be accomplished.

As the manager sets a goal, they establish agreed-upon performance expectations and a realistic timeline for achieving that goal. The manager also explains the method for tracking the team member’s progress toward goal achievement and how often this tracking will take place.

Here’s an example. Michelle is a new hire whose manager, using the Directive leadership style, sets a goal for her to complete a large proposal three weeks from today. They schedule meetings for every Tuesday and Thursday along the way to track her progress toward her goal. Why? Because the odds of Michelle delivering a high-quality proposal are greatly increased if her manager regularly reviews the project and subsequently either praises Michelle’s progress or redirects her efforts to keep her moving in the right direction. Her manager works side by side with Michelle to set her up for success — and she achieves her goal within the established timeline.

How are you when it comes to establishing clear timelines for your people and making time to discuss how things are going?

Identifying Priorities

The Identifying Priorities subscale provides information about how frequently the leader initiates conversations about which goals and tasks are more important than others in a specific performance period.

If someone doesn’t seem to be performing at the level you expect, it’s possible the cause is not a lack of skill or motivation. Many times, the reason people don’t meet performance expectations is that the order in which they prioritize their tasks is much different from the way their manager would have them do it.

An exercise we have conducted many times in various organizations bears this out. We call it the Top Ten Exercise. We ask an individual team member and their leader to make separate lists about the person’s top priorities.

When the two compare lists, the problem becomes obvious. Leaders tell people they’ll hold them accountable for end results such as sales, service, and so on. But the things leaders talk to their people about day in and day out — the things that stick in their minds — are routine tasks.

The great news is that this exercise can be the beginning of a mutually beneficial conversation in which you and each of your people work together, one on one, to identify the person’s priorities in a way that not only sets them up for success, but also confirms to them that you are there to help them achieve their goals.

An aligned purpose and clear expectations are the foundation of an effective work environment.

How would you evaluate yourself on making sure people’s priorities are on track and on target?

Clarifying Roles

The Clarifying Roles subscale provides information on how frequently the leader meets with each team member to discuss key areas of responsibility and limits to autonomy/authority, and to clarify how decisions will be made.

A big part of being a manager is saying “I’ve done what I can do; now I need to turn it over to people so they can be accountable and responsible for their own performance.”

Autonomy, when correctly implemented, is a gradual and appropriate empowering of people and loosening of the reins to enable them to take responsibility for what they are doing.

If managers empower people without building their skills or abilities or providing boundaries, they are abdicating responsibility and setting people up to fail. Autonomy needs to be a slow and steady process. Your goal as a manager is to help people learn their job inside and out through comprehensive training— and then, as they demonstrate competency, give them the autonomy to be flexible.

The challenge for a manager is to identify the point at which to turn a job over to the employee. This is the leap of faith when leaders move from a coaching role to a more consultative role with their people. When managers hang on too long, they can create dependence or worse — a sense of frustration, anger, or resentment if employees feel they are being micromanaged.

How are you at preparing your people to take the lead while still providing support and direction as they are learning?

Developing Action Plans

The Developing Action Plans subscale provides information about how frequently the leader meets with each team member to discuss and formulate action plans and/or a path for learning new skills.

Managers are in a great position to offer this much-needed support to their people, many of whom already have either a formal or an informal development plan for themselves. If you are a manager, here are a few suggestions you can make to help your people progress toward their goals.

- Suggest they consider specifically how their learning and development goals will make them more effective at work

- Have them identify one or two behaviors they want to hone and think of where they might practice those behaviors on the job. For instance, they could practice during One on One meetings with you or in weekly team meetings with their peers

- Keep development top of mind. Regularly touch base with your people on their progress. Ask them to set a specific date by which they will share a success story with you on how they successfully implemented their learning

Being someone’s support system doesn’t have to take a lot of time or effort. Cheering on a direct report and letting them know you care about their growth and development can make a huge difference in their success. After all, what is your goal as an SLII® leader? To help your people achieve their goals.

How would you rate yourself in this area?

Monitoring and Tracking Performance

The Monitoring and Tracking Performance subscale provides information about how frequently the leader meets with each team member on how and to what extent the person’s performance will be monitored and measured.

The concept of development level-based meetings leads into one of the most important — and mutually fulfilling — parts of SLII® leadership: One on One meetings. At least once every two weeks, managers hold a 15- to 30-minute meeting with each of their people.

As a leader, it’s important for you to schedule these check-in meetings in a frequency based on the individual’s development level on a current task or goal. When a task is new to a person, you need to meet often to give specific direction for the first few weeks. After they have a bit of experience behind them, the meetings can be two or three times a week to focus on the goal.

As they become more confident and competent, once a week is probably enough and can involve mainly listening on your part. After the person is on top of the task, regular meetings may not even be necessary unless they choose to request your help.

One benefit of more frequent meetings is the positive effect it has on year-end performance reviews. An SLII® leader who works closely with team members will find that when check-in meetings are scheduled according to development level, open and honest discussions about performance take place on an ongoing basis. This creates mutual understanding and agreement. If these meetings are effective, the year-end performance review is just that: a review of what has already been discussed instead of an after-action report on what should have occurred throughout the year.

How are you at monitoring and tracking performance on a regular basis?

A Final Word on Directive Behaviors

Directive SLII® micro-skills include leadership behaviors such as setting SMART goals, showing and telling how, establishing timelines, identifying priorities, and clarifying roles. These are actions that shape and control what, how, and when things are done. SLII® leaders call on these directive skills when direct reports are in the first stages of learning a new task or working on a goal — when their competence is relatively low and they need specific direction.

Next, we will look at Supportive Leadership Behaviors.

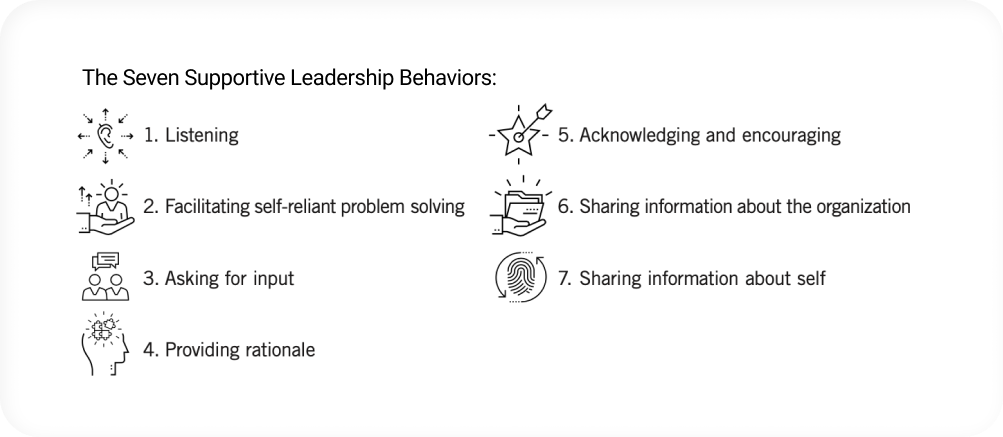

Supportive Leadership Behaviors

Supportive Leadership Behaviors are actions that develop mutual trust and respect, resulting in increased motivation and confidence. Leaders who have high Supportive Leadership Behavior scores consistently listen, facilitate problem solving, ask for input, explain why, and encourage. The Seven Supportive Leadership Behaviors:

Listening

The Listening subscale provides information about how frequently the leader takes time to listen to the concerns of each team member and whether or not those concerns are job related.

Research published by Wendell Johnson in Harvard Business Review showed that because of how our brains work, people think much faster than they talk. As we listen to someone talk, we have time to think of things other than what the person is saying. As a result, we end up listening to a few thoughts of our own in addition to the words we’re hearing the other person speak. Usually we can get back to what the person is saying, but sometimes we listen to our own thoughts too long and miss part of the other person’s message.

To sharpen your listening skills, learn how to resist the temptation to jump in by paying attention to body language and asking questions. Watch a person’s face and body movements as they speak. Are they avoiding eye contact? What about the tone of their voice — do you hear confidence, eagerness, or perhaps irritation? Be sensitive to clues that their silent behaviors provide and be aware of your own nonverbal signals.

Now demonstrate your increased understanding and reflect the other person’s feelings by paraphrasing and summarizing what you heard. Acknowledge any emotions the person is expressing and show them you understand by stating their message back to them in a nonjudgmental way. This demonstrates that you not only understand what they are trying to express but also empathize with their feelings.

Listening is a critical leadership behavior.

When you think about your current listening skills in a work context, how would you describe your current skill level?

Facilitating Self-Reliant Problem Solving

The Facilitating Self-Reliant Problem Solving subscale provides information about how frequently the leader helps each team member explore alternative solutions, and the pros, cons, and consequences of those alternatives, without giving a specific solution.

If you want the people you’re leading to be strong and resilient, you may need to teach them how to solve their own problems. This can be one of the hardest challenges for leaders, because most of us have risen to our positions by being great problem solvers. We’re good at identifying problems, coming up with solutions, and making improvements. However, those very strengths can be weaknesses when it comes to developing resilient team members.

Resist the urge to rescue team members by providing them the solutions to problems. Instead, ask them open-ended questions to lead them through the process of solving the problem on their own. Follow these steps:

- Ask the person to define the problem in one sentence.

- Help them brainstorm options of addressing the problem.

- Ask them to list the pros and cons of these various courses of action.

- Cheer them on as they work toward solving the problem.

Many leaders shun this approach because it requires an initial investment of time and energy. If you catch yourself thinking “Forget it—it will be easier and faster to do it myself,” you’ll know you need to pay special attention to this area.

With this new understanding, how would you evaluate your skill at facilitating self-reliant problem solving?

Asking for Input

The Asking for Input subscale provides information about how frequently the leader seeks ideas and input from each team member regarding work issues and decisions.

Why should a leader regularly ask their people for input? There are multiple reasons.

Asking for input engages your people. The Gallup organization — famous for its employee engagement research — has long recognized that one of the primary reasons employees become disengaged is that they feel their thoughts and opinions don’t count. This disengagement has a significant negative impact on productivity and the bottom line. Whether it’s on a small project or a large change effort, the principle is the same: by asking for input, leaders can turn disinterested employees into engaged ones.

Asking for input sets up a mutual two-way conversation. In the old days, leading was regarded as a top-down relationship. Today, we recognize that leading is more of a side-by-side endeavor, where leader and team member work together to create results. Asking team members for input reduces the chance of miscommunication. For example, suppose you’ve just given instructions on an assignment to someone. To ask for input, you might say, “I’ve been talking for a while and I’d like your feedback. What am I missing?”

Asking for input stimulates people’s best thinking. These days, people often know more about their jobs than their managers do. They also have far more power and potential to contribute to the organization than leaders may realize. From the 3M Post-it® Note to the Starbucks Frappuccino®, stories abound about employee innovations that went on to become multimillion-dollar revenue earners.

If leaders don’t ask for input and value that input, they may be hurting their organization more than they know. Keep in mind that when Steve Wozniak was an engineer for Hewlett-Packard, he tried five times to get managers interested in his idea for a personal computer. Wozniak finally left HP, teamed up with Steve Jobs, and founded a little company named Apple. Talk about a missing some good input!

How are you doing when it comes to asking for input?

Providing Rationale

The Providing Rationale subscale provides information about how frequently the leader explains the reasons for various decisions and actions

Nobody wants to do meaningless tasks. Sometimes, without a bigger perspective, certain tasks may seem confusing — or worse, pointless. People who aren’t given reasons for a request are more likely to ignore or resist that request.

By providing rationale, you answer the question why. Take time to explain to people the reasoning behind a request and how their work will help achieve larger goals. Give people a mental picture of what’s needed. What will it look like if what they would like to see happen actually does happen?

If you simply assign a task without giving a reason, the person is left to guess why you made the request. That’s demotivating; they may wonder why they should bother to do it at all.

Also, assigning a task without providing rationale doesn’t allow the person to apply their own knowledge and skills to analyze and solve the problem. They’re not called to stretch and grow. Their creativity is stifled. Consequently, they aren’t invested in the result. Not only does this undervalue the individual, it also hurts the organization.

So when you assign a task or project, remember to provide a rationale. Because when you answer the question why, people will be better equipped to step up and help make the organization a success.

How would you evaluate yourself in this important area?

Acknowledging and Encouraging

The Acknowledging and Encouraging subscale provides information about how frequently the leader meets with each team member to express appreciation, provide feedback, or value the team member's contribution.

In the talks he gives around the world, best-selling business author Ken Blanchard often asks audiences: “How many of you are sick and tired of all the praisings you get at work?” Everybody laughs, because to most of us, praising does not come naturally, and we don’t generally hear much praise. Thousands of years of evolution have wired our brains to search for what isn’t right: Is that a stick on the trail or a venomous snake? Is the wind moving that bush, or is it a bear? Our tendency to focus on what isn’t right is a protective mechanism. Unfortunately, it makes us more likely to catch each other doing things wrong.

That’s why, of all the supportive SLII® behaviors, Ken Blanchard’s favorite is Acknowledging and Encouraging. He has often said that if he could only use one management tool for the rest of his life, it would be this: Catch People Doing Things Right.

Too often people feel they are working in a vacuum because no matter how well they perform, nobody notices. Or, if their manager notices, they make overly general comments, such as, “I appreciate your efforts” or “thanks for the good job.” While that’s better than saying nothing, it doesn’t do a whole lot to motivate the person or help that person feel valued.

Acknowledging people’s efforts and encouraging their progress sets up a positive cycle: Your praise helps people feel good about themselves. People who feel good about themselves produce good results— for themselves, their teams, and the organization.

How are you at praising?

Sharing Information about the Organization

The Sharing Information about the Organization subscale provides information about how frequently the leader shares facts about marketplace trends and the organization's strategies, policies, finances, or personnel, which are relevant to each team member's goals and success.

Successful leaders know how to create a partnership with the people they lead. They view people as working with them rather than for them. Managers skilled in SLII® don’t just tell people what to do; they actually provide resources and information to help people do their jobs.

When employees are able to learn more about their organization, they can see where their individual work fits into a larger context. They work faster and smarter because now they have access to organizational resources and knowledge. Knowing their tasks have meaning and connect to a larger purpose boosts people’s motivation and increases their job satisfaction.

Being transparent with information about your organization — even information on sensitive topics such as future business strategies, financial data, industry issues, or problem areas — communicates a sense of “we’re in this together.” This kind of information sharing builds trust and improves morale. It also encourages people to act like owners of the organization, which ultimately improves the bottom line.

When leaders share information about the organization, they multiply the number of intelligent minds working to solve problems.

How are you when it comes to sharing business information with others?

Sharing Information about Self

The Sharing Information about Self subscale provides information about how frequently the leader shares information and insights about their personal experience to broaden each team member's perspective on their own work.

Like many skills, there’s a right way and a wrong way to share information about yourself in a work setting. Use good judgment when sharing information about yourself. Remember, the purpose of sharing about yourself is to foster a thriving partnership. It’s not about you; it’s about creating connection.

Keep the focus on sharing information that will be useful to the person you’re leading. The information you share should put them at ease and help them relate to you. Do not waste people’s time by oversharing or disclosing personal information that could make people uncomfortable.

Before you disclose personal information, ask yourself: Will this information serve the person I am leading? Perhaps you have a personal anecdote that can help someone understand why a task is important. Maybe you have a story about an error you made that can illustrate why a certain policy or procedure makes sense. It can be helpful to share your mistakes with others so that they don’t have to learn the hard way.

So — with others’ best interests in mind — when it comes to sharing information about yourself with your team, how would you evaluate yourself?

A Final Word on Supportive Behaviors

Supportive SLII® micro-skills include leadership behaviors such as listening, facilitating self-reliance, asking for input, providing rationale, acknowledging, and encouraging— plus sharing information about self and the organization. These are actions that develop mutual trust and respect, resulting in increased motivation and confidence.

SLII® leaders call on these supportive skills when direct reports are in the later stages of learning a task or working on a goal — when their competence is relatively high and they need support to continue their growth and development.

In our final section, we will look at how you scored yourself and discuss next steps in your development as an SLII® leader.

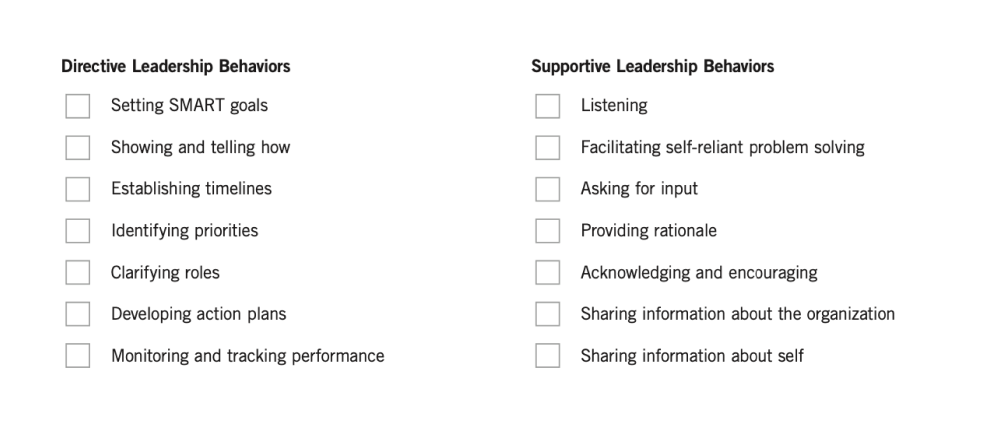

Strengths & Weaknesses

How did you evaluate yourself across the seven Directive and seven Supportive leadership behaviors?

Put a + by the areas where you considered yourself Exceptional. Put a — by the areas that Need Work. Which are easier for you to provide — Directive or Supportive behaviors?

Modifying Your Style to the Needs of Your People

The best leaders are those who adjust their style to meet the needs of their people. Blanchard research conducted with tens of thousands of leaders has found that only 1% of leaders are able to successfully match the needs of all four development stages: Enthusiastic Beginner; Disillusioned Leader; Capable, but Cautious, Contributor, and Self- Reliant Achiever. A full 54% of leaders use their default style with everyone, regardless of their development level — some through choice and others due to lack of awareness and lack of training.

Our guess is that you fall into the latter category — no one ever asked you about your default leadership style before. But now you know, and the next question is, ”How can I improve?”

Awareness is the first step. Are Directive behaviors more suited to your leadership style, or are you more inclined to use Supportive behaviors? What about others in your organization? What are their preferred leadership behaviors?

What comes easy for them? Which one would they consider their natural style? Consider creating a discussion group to talk about it!

Next, consider what this means for the people who report to you.

How do you work with people who are new to tasks versus people who are very experienced? Can you see how some behaviors didn’t serve you well in the past when you worked with people who didn’t match up with your natural style? How about people you are currently working with?